Moving in Together (Till Death do us Part),

2008

Stefanie Schneider

Photography : C-print

160 x 320 x 0.1 cm 63 x 126 x 0 inch

Second NOT DISPLAYED BLUR TEXT

Free returns within 14 days

Authenticity guaranteed

Learn moreSecure payment

About the artwork

Type

Numbered and limited to 5 copies

1 copy available

Signature

Signed artwork

Authenticity

Sold with certificate of Authenticity from the artist

Invoice from the gallery

Medium

Dimensions cm • inch

160 x 320 x 0.1 cm 63 x 126 x 0 inch Height x Width x Depth

Framing

Silver aluminium aluminium mounted

Artwork dimensions including frame

160 x 320 x 0.3 cm 63 x 126 x 0.1 inch

Tags

Artwork sold in perfect condition

Artwork location: United States

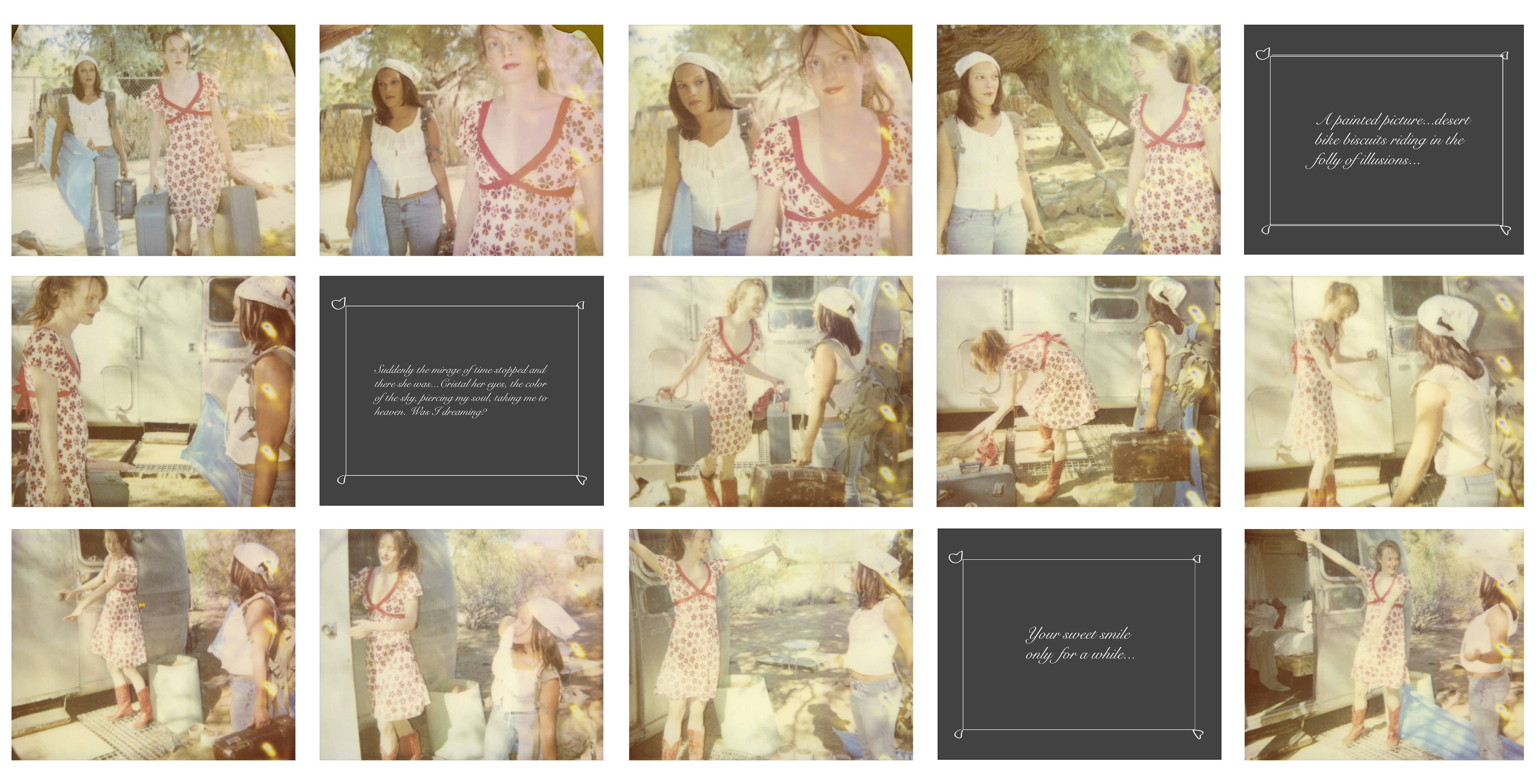

'Moving in Together', 2008

15 analog C-Prints analog C-Prints, hand-printed by the artist on Fuji Crystal Archive Paper, based on an expired Polaroid, mounted on Aluminum with matte UV-Protection, signed on verso.

Edition 1/5. 160 x 320 cm installed. 50x60 each piece. Artist Inventory No. 8533.01.

This piece was exhibited at:

2008 29 Palms, CA, Galerie Spesshardt-Klein, Berlin (S)

Stefanie Schneider’s Till Death Do Us Part

or “There is Only the Desert for You.”

BY DREW HAMMOND

Stefanie Schneider’s Til Death to Us Part is a love narrative that comprises three elements:

1. A montage of still images shot and elaborated by means of her signature technique of using Polaroid formats with outdated and degraded film stock in natural light, with the resulting im ages rephotographed (by other means) enlarged and printed in such a way as to generate further distortions of the image.

2. Dated Super 8 film footage without a sound track and developed by the artist.

3. Recorded off-screen narration of texts written by the actors or photographic subjects, and selected by the artist.

At the outset, this method presupposes a tension between still and moving image; between the conventions about the juxtaposition of such images in a moving image presentation; and, and a further tension between the work’s juxtaposition of sound and image, and the conventional relationship between sound and image that occurs in the majority of films. But Till Death Do Us Part also conduces to an implied synthesis of still and moving image by the manner in which the artist edits or cuts the work.

First, she imposes a rigorous criterion of selection, whether to render a section as a still or moving image. The predominance of still images is neither an arbitrary residue of her background as a still photographer—in fact she has years of background in film projects; nor is it a capricious reaction against moving picture convention that demands more moving images than stills. Instead, the number of still images has a direct thematic relation to the fabric of the love story in the following sense. Stills, by definition, have a very different relationship to time than do moving images. The unedited moving shot occurs in real time, and the edited moving shot, despite its artificial rendering of time, all too 2009often affords the viewer an even greater illusion of experiencing reality as it unfolds. It is self-evident that moving images overtly mimic the temporal dynamic of reality.

Frozen in time—at least overtly—still photographic images pose a radical tension with real time. This tension is all the more heightened by their “real” content, by the recording aspect of their constitution. But precisely because they seem to suspend time, they more naturally evoke a sense of the past and of its inherent nostalgia. In this way, they are often more readily evocative of other states of experience of the real, if we properly include in the real our own experience of the past through memory, and its inherent emotions.

This attribute of stills is the real criterion of their selection in Til Death Do Us Part where consistently, the artist associates them with desire, dream, memory, passion, and the ensemble of mental states that accompany a love relationship in its nascent, mature, and declining aspects.

A SYNTHESIS OF MOVING AND STILL IMAGES BOTH FORMAL AND CONCEPTUAL

It is noteworthy that, after a transition from a still image to a moving image, as soon as the viewer expects the movement to continue, there is a “logical” cut that we expect to result in another moving image, not only because of its mise en scène, but also because of its implicit respect of traditional rules of film editing, its planarity, its sight line, its treatment of 3D space—all these lead us to expect that the successive shot, as it is revealed, is bound to be another moving image. But contrary to our expectation, and in delayed reaction, we are startled to find that it is another still image.

One effect of this technique is to reinforce the tension between still and moving image by means of surprise. But in another sense, the technique reminds us that, in film, the moving image is also a succession of stills that only generate an illusion of movement. Although it is a fact that here the artist employs Super 8 footage, in principle, even were the moving images shot with video, the fact would remain since video images are all reducible to a series of discrete still images no matter how “seamless” the transitions between them.

Yet a third effect of the technique has to do with its temporal implication. Often art aspires to conflate or otherwise distort time. Here, instead, the juxtaposition poses a tension between two times: the “real time” of the moving image that is by definition associated with reality in its temporal aspect; and the “frozen time” of the still image associated with an altered sense of time in memory and fantasy of the object of desire—not to mention the unreal time of the sense of the monopolization of the gaze conventionally attributed to the photographic medium, but which here is associated as much with the yearning narrator as it is with the viewer.

In this way, the work establishes and juxtaposes two times for two levels of consciousness, both for the narrator of the story and, implicitly, for the viewer:

A) the immediate experience of reality, and

B) the background of reflective effects of reality, such as dream, memory, fantasy, and their inherent compounding of past and present emotions.

In addition, the piece advances in the direction of a Gesammtkunstwerk, but in a way that reconsiders this synaesthesia as a unified complex of genres—not only because it uses new media that did not exist when the idea was first enunciated in Wagner’s time, but also because it comprises elements that are not entirely of one artist’s making, but which are subsumed by the work overall. The totality remains the vision of one artist.

In this sense, Till Death Do Us Part reveals a further tension between the central intelligence of the artist and the products of other individual participants. This tension is compounded to the degree that the characters’ attributes and narrated statements are part fiction and part reality, part themselves, and part their characters. But Stefanie Schneider is the one who assembles, organizes, and selects them all.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THIS IDEA (above) AND PHOTOGRAPHY

This selective aspect of the work is an expansion of idea of the act of photography in which the artistic photographer selects that which is already there, and then, by distortion, definition or delimitation, compositional and lighting emphasis, and by a host of other techniques, subsumes that which is already there to transform it into an image of the artist’s contrivance, one that is no less of the artist’s making than a work in any other medium, but which is distinct from many traditional media (such as painting) in that it retains an evocation of the tension between what is already there and what is of the artist’s making. Should it fail to achieve this, it remains, to that degree, mere illustration to which aesthetic technique has been applied with greater or lesser skill.

The way Til Death Do Us Part expands this basic principle of the photographic act, is to apply it to further existing elements, and, similarly, to transform them. These additional existing elements include written or improvised pieces narrated by their authors in a way that shifts between their own identities and the identities of fictional characters. Such characters derive partially from their own identities by making use of real or imagined memories, dreams, fears of the future, genuine impressions, and emotional responses to unexpected or even banal events. There is also music, with voice and instrumental accompaniment. The music slips between integration with the narrative voices and disjunction, between consistency and tension. At times it would direct the mood, and at other times it would disrupt.

Despite that much of this material is made by others, it becomes, like the reality that is the raw material of an art photo, subsumed and transformed by the overall aesthetic act of the manner of its selection, distortion, organization, duration, and emotional effect.

* * *

David Lean was fond of saying that a love story is most effective in a squalid visual environment. In Til Death Do Us Part, the squalor of the American desert violated by the detritus of consumerism, cheap construction, and its unrelenting light, is so extreme that advertising clips have elevated it to an iconographic status that has become a convention.

But unlike the boast of advertising’s scrupulous control of the image in the service of a product, Stefanie Schneider’s work repudiates such control by means of an intentional imposition of accident. Since her source images derive from a degraded Polaroid film stock long past its expiration date—these images are then reprocessed and enlarged on analog equipment—the presence of the distortions in the images are intended by the artist who chooses the stock precisely for its capacity to distort, but the nature of the distortions, within the range of what the film stock in operation by the artist can generate, remain accidental and only visible to the artist for selection after the fact.

Besides that such images evoke a tension between accident and control that is alien to commercial images that must be controlled due to the contractual nature of their origins and aims, it is a fact that the way accident underlies these images, does not derive from “what is already there” in, the conventional sense that photographs are constrained by the way they necessarily capture existing reality external to the artist’s contrivance. Here the accident is in the intrinsic process: it is chemical, physical, mechanical, and concealed from the artist’s view, as much as the artist does contrive the conditions for it to occur. In this sense, it perverts this traditional limitation of photography as an artistic medium by exaggerating it to an extreme degree. It transfers the lack of an artist’s contrivance, from the a priori nature of that which is photographed, to a chaotic element in the mechanico-chemical process of reproduction.

This intentional imposition of accident reveals a marked precedent in the Abstract Expressionist painting of the mid-20th Century. The great figures of Abstract Expressionism all devised a way of applying pigment by means of a technique that incorporated a degree of accident into the process. It is this theoretical feature derived from practice that most effectively unites their work its conceptual aspect, despite the overt formal dissimilarity between the works. Pollock dripped and flung pigment, but mostly did not actually touch his brush to the canvas; de Kooning squeezed pigment onto the canvas directly from the tube, and scraped it behind the blade of a putty knife where its application was concealed from his own view; Frankenthaler would bleed thinned paint onto an unprimed canvas whereby the precise form and extension of the interaction would be self-generated; and Bacon, in another world across the Atlantic, differed from Soutine not as much in form as in technique: he would not paint his distortions directly with a brush, but would smudge them with a rag or sponge so that the result was invisible until after the fact.

The Minimalists who followed, rejected this sort of work as too “gestural,” too “representational,” and too “personal,” but, all too often they ignored or underestimated the power of the tension to be derived from this conceptual dimension of the work in its simultaneous accommodation of intention and accident—which, in either case they would have regarded as inimical to the absolute control they often fetishized as an alternative to traditional emotion.

But it is precisely this intentional imposition of accident that Stefanie Schneider introduces to the photographic medium in the intrinsic manner of its rendering. In this sense, her work is radically distinct from a photography that is thoroughly “staged,” or merely altered after the fact, or “manipulated” in the reproduction process, or degraded on its surface, or for that matter which luckily captures an accidental event. Her work reveals a marked theoretical kinship with the work of painters of the forties and fifties, by appropriating or “selecting” their most pertinent conceptual innovation and adapting it for the photographic medium by devising a practical means to incorporate it in a medium that is itself mechanically and chemically mediated.

Here, the desert in all its squalor, is neither entirely real, nor “hyper-real,” but a fictive environment generated by the artist’s contrivance through the imposition of accident upon the process of photographic representation.

Stefanie Schneider’s desert is no more literally real than is the absence of any intrusion of the external world in Till Death Do Us Part. The characters seem to have no past or future apart from the immediate—one could say in this regard, hellish— all-present of their exclusive relationship, and the narrated allusions to events that may or may not be real in the imaginary plane the characters inhabit. Within the world of this visual and narrated fiction, there exists for them no opportunity for interaction with anyone but each other, either in person, or by electronic means.

Instead, the artist selects all aspects of their condition, even though constituents of the totality of their condition may originate with the actors themselves. Similarly, the artist isolates them from all elements elements that would fall outside the exclusive domain of their relationship.

In this sense, Till Death Do Us Part is not reality, but more than reality’s depiction can achieve through conventional means, it conveys a real sense of what it is like to be a protagonist of such a relationship, to be prey to the strange delusions that so often occur as part of the relationship’s intrinsic condition, the sense that, for the lovers, only they themselves exist, and they exist only for themselves and for each other.

The fact that both lovers are women, on the one hand, underscores this exclusivity, and renders them more keenly and apparently reflections of each other. On the other hand, it implies a degree of overt harmony in the work’s formal aspect that itself generates an aesthetic counterpoint to the tension between intention and accident in the work’s conceptual aspect.

The effaced death that ends the work reaffirms the sense of oscillation between reality and fantasy that permeates the work. In the end, it is as though the totality of both character’s passions were subsumed by the desert, the stage upon which the artist enacts every mental state she conjures.

----------------

Stefanie Schneider lives and works in the California High Desert and Berlin

Stefanie Schneider's scintillating situations take place in the American West. Situated on the verge of an elusive super-reality, her photographic sequences provide the ambience for loosely woven story lines and a cast of phantasmic characters.

Schneider works with the chemical mutations of expired polaroid film stock. Chemical explosions of color spreading across the surfaces undermine the photograph's commitment to reality and induce her characters into trance-like dreamscapes. Like flickering sequences of old road movies Schneider's images seem to evaporate before conclusions can be made - their ephemeral reality manifesting in subtle gestures and mysterious motives. Schneider's images refuse to succumb to reality, they keep alive the confusions of dream, desire, fact, and fiction.

Stefanie Schneider received her MFA in Communication Design at the Folkwang Schule Essen, Germany. Her work has been shown at the Museum for Photography, Braunschweig, Museum für Kommunikation, Berlin, the Institut für Neue Medien, Frankfurt, the Nassauischer Kunstverein, Wiesbaden, Kunstverein Bielefeld, Museum für Moderne Kunst Passau, Les Rencontres d'Arles, Foto -Triennale Esslingen.

About the seller

Professional art gallery • United States

Artsper seller since 2019

Vetted Seller

This seller rewards your purchases of multiple artworks

Imagine it at home

Discover more by the artist

Presentation

Stefanie Schneider (1968) is a German photographer living in Berlin and Los Angeles. Schneider's photographs exhibit the appearance of expired Polaroid instant film, with its chemical mutations. It has been released in books and exhibition catalogs, and in her own feature film 29 Palms, CA (2014). Her work has also been used as the cover art for music by Red Hot Chili Peppers and Cyndi Lauper, and in the film Stay (2005).

Schneider's preferred choice of location is the American West (especially Twentynine Palms, California, which served as location and title to one of her books), and the mounting of sequential images in a panel, the photographs evoke the impression of faded dreamy film stills. She holds an MFA in photography from the Folkwang Hochschule in Essen, Germany.

Schneider completed 29 Palms, CA in 2014. A feature film, art piece that explores the dreams and fantasies of a group of people who live in a trailer community in the Californian desert. The project includes six films: "Hitchhiker", "Rene's dream", "Sidewinder", "Till death do us part", "Heather's dream" and the feature film "The Girl Behind the White Picket Fence". A defining feature is the use of still Polaroid images in succession and voice over. Characters talk to themselves about their ambitions, memories, hopes and dreams. The latest of these short film is "Heather's dream", starring Heather Megan Christie and Udo Kier, and was selected in May 2013 by the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen and is also nominated for the 2013 German short film award.

In a review of her book Stranger Than Paradise, Daniel Kothenschulte writes in the German magazine Literaturen that:

Stefanie Schneider is an internationally known artist that takes analog photographs and makes experimental movies with them. Schneider has cribed some of the titles of the series of her enlarged Polaroids from her favorite movies: Red Desert, Zabriskie Point or The Last Picture Show. Even if most images remain connected to the genre of road movies—in one case one seems to get a glimpse of Ridley Scott's tragic runaways Thelma and Louise.

Collections

DZ Bank, Francfort, Allemagne

Dreyfuss, Bâle, Suisse

Schmidt Bank, Ratisbonne, Allemagne

Groupe d'édition Holtzbrinck, Stuttgart, Allemagne

Collection Sander, Berlin, Allemagne

Ocean Foundation, Zurich, Suisse

Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, Allemagne

Impossible Collection, Vienne, Autriche

Collection Luc LaRochelle, Montréal, Canada

Collection d'art du canton de Zug, Suisse

Expositions

Expositions individuelles

2014 Motion Photography – 6 Finalists, Saatchi Gallery, Londres, GB

2014 Instantdreams, De Re Gallery, Los Angeles, USA

2014 Stefanie Schneider, c.art-Galerie Bregenz, Autriche

2013 The girl behind the white picket fence, Galerie Catherine et André Hug, Paris, France

2012 Stranger than Paradise, Christian Hohmann Fine Art, Palm Desert, USA

2012 Stefanie Schneider, Gallery at Cliff Lede Vineyards, Napa Valley, USA

2011 California Dreaming, ROLLO Contemporary, Londres, GB

2010 Stefanie Schneider, Galerie Walter Keller, Zurich, Suisse

2010 Instant Dreams, Frank Picture Gallery, Santa Monica, USA

2009 29 Palms, CA, Moravian Gallery, Brno, République tchèque

2008 Sidewinder, Städtische Galerie am Mozartplatz, Salzbourg, Autriche

2007 Wastelands, Kunstverein Recklinghausen, Allemagne

2006 Wastelands, Zephyr / Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen, Mannheim, Allemagne

2005 Last Picture Show, Galerie Caprice Horn, Berlin, Allemagne

2004 Suburbia, Galerie Kuttner Siebert, Berlin, Allemagne

2004 Stefanie Schneider, Galerie Michael Sturm, Stuttgart, Allemagne

Expositions collectives

2014 Nude, Pop-up Art Gallery Berlin, Allemagne

2013 Images for Images, GASK – Gallery of the Central Bohemian Region, Kutná Hora, République tchèque

2013 The Polaroid Years: Instant Photography and Experimentation, Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Poughkeepsie, USA

2013 Road Atlas - Straßenfotografie, DZ Bank Collection, Kunsthalle Erfurt, Allemagne

2012 Polaroid (Im)Possible – The Westlicht Collection, Forum de la culture et de l'économie du land de Rhénanie du Nord-Westphalie, Düsseldorf, Allemagne

2010 Mapping Worlds: Welten verstehen – Aufbruch in die Gegenwart, 8ème triennale internationale de la photo, Esslingen, Allemagne

2009 True Lies, Kunsthaus Essen, Allemagne

2008 Les Rencontres d'Arles, organisées par Christian Lacroix, nominée pour le prix découverte

2007 Breaking the Waves, Arthaus, Los Angeles, USA

2006 Artists for Tichy - Tichy for Artists, Museum für Moderne Kunst, Passau, Allemagne

2006 Out of the Camera: Analoge Fotografie im digitalen Zeitalter, Kunstverein, Bielefeld, Allemagne

Land in Translation, Riverside Museum, USA.

Artsper delivers internationally. The list of countries is available in the first step of your cart.

If your country is not listed contact us at [email protected] and we will see what we can do.

Note that Customs fees may apply for works shipped internationally. This is indicated in the first step of the shopping cart.

You can choose a delivery address different from the billing address. Make sure that a trusted person is present to receive the work if you cannot be there.

Have you purchased a painting, sculpture or work on paper?

Find our expert advice for the conservation and promotion of your works in the articles below:

Artsper offers you access to more than 200,000 works of contemporary art from 2,000 partner galleries. Our team of experts carefully selects galleries to guarantee the quality and originality of the works.

You benefit from:

-

Works at gallery price

-

Return within 14 days, regardless of your location

-

Easy resale of the work purchased on Artsper

-

Personalized research tools (selection and tailor-made universe)

Our customer service is available for any assistance.

At Artsper, our mission is to allow you to collect works of art with complete peace of mind. Discover the protections we offer at every stage of your shopping experience.

Buy works from top galleries

We work in close collaboration with carefully selected art galleries. Each seller on Artsper is carefully examined and approved by our team, thus ensuring compliance with our code of ethics. You therefore have the assurance of purchasing authentic, high-quality works.

Total transparency: you know what you are buying

Before being posted online, all artwork on Artsper is reviewed and validated by our moderation team. You can browse with complete peace of mind, knowing that each piece meets our criteria of excellence.

Personalized support: our experts at your service

Our team of contemporary art experts is available by phone or email to answer all your questions. Whether you want advice on a work or a tailor-made selection to enrich your collection, we are here to support you.

Resell your works with ease

If you have purchased a work on Artsper and wish to resell it, we offer you a dedicated platform to relist it. To find out more, click here.

Make offers with Artsper: negotiate like in a gallery

You have the possibility to propose a price for certain works, just like in a gallery. This feature allows you to initiate discussions and potentially acquire your coins at advantageous prices.

Get help with your negotiations

Our team will negotiate for you and inform you as soon as the best offer is obtained. Do not hesitate to call on our expertise to ensure a transaction at the best price.

Order securely

Artsper satisfaction assurance

We want you to be completely satisfied with your purchase. If the work you receive is not to your liking, you have 14 days to return it free of charge, and you will be refunded in full, whatever the reason.

Secure payment with Artsper partners

All credit card payments are processed by Paybox, the world leader in payment solutions. Thanks to their strict security standards, you can transact with confidence.

Problem Support

In the rare event that an artwork arrives damaged or not as described, we are here to help. Whether for a return, refund, restoration or exchange, our team will support you throughout the process and will ensure that we find the solution best suited to your situation.

Conditions to benefit from Artsper protections:

-

Use one of the payment methods available on Artsper for your order.

-

Report any problems within one week of receiving the work.

-

Provide required photographic evidence (including original artwork and packaging).

Artsper guarantees cover the following cases:

-

The received work lacks a described characteristic (for example, a signature or frame).

-

The artwork has significant differences from its description (e.g. color variation).

-

The work is damaged upon receipt.

-

The work is lost or damaged by the carrier.

-

Delivery is significantly delayed.

With Artsper, you collect with complete peace of mind.